I once did time in a provincial reformatory for shooting a guy. It’s a bit of a long story but the gist of it was I was attacked from behind and beaten with nunchucks over a girl. Not any girl, she was runner-up Miss Nude Ottawa and a good friend of mine. I wasn’t even fucking her, then.

To shorten the story, the owner took a dislike to me sitting there with all the strippers at my table drinking and snorting lines with the girls. I ended up a little drunk with a high school buddy who happened to come in looking to see pussy. The owner waited until the afternoon lull before picking a fight, then siccing the headwaiter on me from behind with nunchucks. I went down but not out and left.

I came back and shot one of them and tried to kill the other one. Fucker kept throwing beer cases at me and hiding behind people as I fired, until I had only one bullet left which I kept to cover my exit.

I got away but turned myself in a few days later once the cops had raided everyone I knew. I was holed up at a gal’s place who was not my girlfriend, being looked after. From there, I arranged arrest on my terms, after a hospital visit with my lawyer to sew up my head 48 hours after I was injured, something rarely done..

I got bail after a few days, thanks to my brothers and sisters stepping up to vouch for me. This despite my having not lived at home for several years. It was also the one time my folks were not in town I found out later. My eldest brother even pledged his motorcycle as surety for bail. I guess you could do that in those days. We used a lot of the “out of character” phrase, a mantra for some time afterwards.

At the preliminary, I was suddenly thrust into a waiting room at #1 Nicholas Avenue with all the people who were going to testify against me. So, I went downstairs with my gal to the coffee shop and bought about 30 coffees and sandwiches to serve my witnesses. While asking if they needed creamers or sugar, I had a chance to give them my side of the story, impressing upon them this was “out of character” and resulted from being attacked first.

Not only that, the guy who had hit me from behind and whom I’d shot, taking out his spleen and leaving a bullet lodged up against his spine, suggested we make a deal. He’d admit he hit me first if I’d testify for him later at a criminal compensation hearing. I agreed.

Whereas my lawyer had told me straight up I’d get at least five years, waving the book with the attempted murder statute under my nose, I ended up with a deuce less. That is two years less a day. Which means I was in a reformatory. No pen time this bit.

As I returned from court and was being re-booked into the county jail’s maximum wing on Innes Road, one of the guards was a little impatient with me as he demanded yet another search at the Max Rotunda. “Turn around, hands against the wall, spread’em,” he said gruffly. I noticed some broad looking at me and stared back her with contempt, thinking she probably liked to see me humiliated in this way.

photo by Wayne Cuddington/ Postmedia

Not an hour went by before I was called out of my cell to speak through the bars at the top of the range to this very lady. Apparently, she was our new classifications officer and wanted to hear my story. Prisons were being staffed by women suddenly in our rush to progress.

Of course, I told her it was all a mistake, that it was an overreaction on my part after being brutally beaten for no reason other than petty jealousy. I did my best to convince her it was “out of character” and told her about my jewelry and furniture businesses.

By the end of the week, I had buddies deliver letters attesting to my businesses and how I was needed outside to keep things afloat. I got out within ten days of being in. The guys on my range—many of whom I knew from the outside—couldn’t believe it. I left them the rest of the hash I’d smuggled in up my ass on the day I was sentenced.

That worked out well for a while. I was in a halfway house out on Riverside, with an apartment on Innes just a few miles down the river. Meanwhile, my buddies had rented a place further out the river for the summer. I bounced between the three places.

Peanut Haven out by Manotick it was called, and I rented half of one of the three cottages with my buddy Flo. Every morning at ten while at the halfway house, I’d dress in a suit and tie, grab my briefcase and go outside to meet my partner. He’d show up in our Cadillac dressed in jeans and a T-Shirt with bulging muscles. He looked like my body guard and we didn’t deny it. Then I’d either go deal dope one place or another, the time away barely causing a ripple in my schedule.

Sometimes, my partner had other shit to do so I’d drive the Caddy around and take care of business myself. It so happened I walked into a buddy’s place to collect some money one evening, just as he was being raided. I’d almost forgot about this until my high school reunion a few months back. Someone there reminded me they were there when it happened.

I knocked on the door and when it opened I saw he was being raided and ran. They caught me on the stairs and found my keys. They searched the block and tried the locks until they found the right one. My partner had left a few ounces of pot tucked into a construction boot in the trunk without me knowing. I was busted.

I remember the ride downtown in the wagon with the other guys. How I had to push my handcuffed arms from behind my back and under me, and how they had helped me get my legs through one at a time, so I was cuffed from in front instead of behind. I remember that.

I was returned to the county bucket and reclassified. I kept telling them it was all a mistake; the pot wasn’t mine and was left there by mistake. It was still, “out of character,” despite how it looked! I even had someone else claim the pot as theirs. We took a shot at it. The guards started calling me “silk.” My poor classification officer gal listened patiently and told me she’d send me to the easiest place possible. I was shipped out to a minimum-security joint.

No sooner than I arrived at what we called Burritts Rapids, I immediately applied for a half-way house. I remember that interview with the warden. He called me a con-artist and reminded me of the silk nickname which had followed in my classification reports from Ottawa. He denied me outright and told me to do my time. I told him I was happy to re-apply again later.

I worked at it. The thing was, you could be denied and re-apply the next day. So that’s what I did. I was turned down over and over for transfer out to the city. And the food at the Rideau Correctional Facility, as it was known officially, was terrible. By far, the worst food I’ve eaten in prison and where I was introduced to hickory tasting coffee. Horrible, I found punishing.

So I aimed for and won a day-job working at a local developmental hospital in Smith Falls. They had those at the time, since closed. I’d be bused to the hospital every morning and spend the day there working as a pool porter. I’d get a voucher where I could eat cafeteria food which was ten times better tasting than joint food. I’d also get to wear my street clothes and talk to women, good smelling gals. I could also swim in the pool if I wanted, with women lifeguards who worked there, and were nice to me! It was a good go, as they say.

It was there I saw what they used to do with all the kids no one wanted. There were kids wards and adult wards, male and female. They even had a series of cottage style buildings where some of the more high-functioning kids could live. I never met anyone from those. Blind, deaf, dumb kids were dumped here by families, encouraged by doctors.

Autistic headbangers occupied whole wards, banging their hockey helmeted heads on the floor all day. Many were in diapers, toddlers who screamed and self-harmed in their self-soothing attempts, but some were older. None of those kids swam that I remember. Or if they did, I was sent to fetch them strapped in a wheelchair and brought them down one at a time.

Several wards held schizophrenics, separated into male and female. Those places were nuts at times, depending on when the meds had been given out. The male wards were tough. I saw attendants dressed in while smacking people in desperation when they were attacked, or someone was stealing an ashtray or a smoke. It was an angry place when meds wore off.

Many Down Syndrome kids and adults lived there. Every developmental issue was represented at the Rideau Regional Centre. If you had never encountered anything like this in your life, the only thing I can reckon it to is the freak shows at the ex. In those days, families gave these kids up to the state, to be institutionalized. The place had to house a thousand, I bet.

Whole wards of alcohol damaged individuals, Korsakoff Syndrome and tardive dyskinesia had a place there. Wards with people in straight jackets for their own protection and the protection of the staff. The developmentally delayed child who lives becomes a developmentally delayed adult in a place like this. Without good stimulation in these warehouse-type institutions of old, it becomes a horror story, far beyond Steinbeck’s, “Of Mice and Men.”

Everyone smoked in the place, and during the day it had clouds of smoke in every hallway and in every dorm, cigarette butts everywhere on the floor. I remember a kid who had really bad brain damage from a car accident. He was one of my first pool-porter patients. Because of him, I learned to walk on the right side of my charges with my left hand on the back of their neck and my right hand folded across my mid-section and holding on to their right forearm. This way I could pivot them one way or another in a hurry.

Big and tall and you could tell, once good-looking, Stephen was pica. And he was addicted to any stimulant, not just tobacco. He once got away from me and ran into a ward and grabbed their instant coffee and started to scoop it into his mouth by the handfuls. The attendants freaked and physically intervened and taught me how to hold on to him.

He’d run through his weekly allotment of smokes in a day or two and nic-fit the rest of the week. He’d gesture to me, two fingers tapping his mouth slowly while saying in a deep and clearly brain-damaged way, “mokee? mokee? moke?” with a twinkle in his eye. Sometimes I’d oblige him, and become his new best friend. He could answer questions about his accident, but it took a great deal of effort. I’d bust his balls about how all the girls must have liked him.

I’d be walking him down the hall to the pool and I’d sense him looking at me out of the corner of his eye, sizing me up, getting just slightly more anxious. First time it happened he broke free and dove upon a cigarette butt on the floor and gobbled it down before I could stop him. After that, I see him start to twitch a bit and look ahead and spot his target, taking precautions.

In one of the male adult wards lived Birdman. Staff would get him up in the morning and dressed. Soon he would strip naked and sit up on the window sill in a crouch for hours and hours. His whole body, from head to toe, would turn blue from the constricted blood vessels while his tongue would dart in and out like a lizard. His penis would hang down over the side as well, a vestigial long dong of blue. He was mostly catatonic, staring off into space.

I happened to be there when a kid with cerebral palsy sued the government for the right to make his own decisions about where to live and how to spend his monthly stipend. I can’t remember his name (Mike?) but he won in Ontario court while we were all pulling for him.

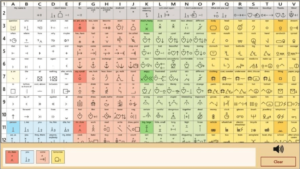

He used a Bliss board, and I had several wonderful conversations with him in his wheelchair, a big board of symbols in front of him like a table, and him awkwardly but effectively using Blissymbolics to communicate. He had a goofy smile and an intelligence in eyes that twinkled easily. I gave him my best props and pep talks as he waited his own reclassification. He was an amazing guy, really inspiring.

Perhaps it was these kids and adults who first awakened in me a dormant caring I’d suppressed on the street for many years. They were doing time like I was, society’s refuse, shuffled aside and locked away. I was a prisoner and so were they. We were on the same side, with me at Rideau Correctional Centre, while they were at the Rideau Regional Centre.

In 2013, the Ontario liberals awarded survivors of the Rideau Centre 20.6 million. David McKillop, then 63, placed there when he was just four years old, was the representative plaintiff. “I got beaten up by staff, sexual assault, everything… You couldn’t do anything about it… You couldn’t say anything about it at that time” he told the CBC after the settlement. “I still dream about memories about it… We’re going to get help for that too. I wanted to make sure the government paid for it, what they did to us.”

Bless your heart my man. Seeing what I saw late 1970s during the day when it was at its busiest, I can only imagine what it was like at night. It’s horrifying to think of now.

It was later while studying behavioural sciences in the late 1980s where I was exposed to the Cornwall project, an initiative to keep developmentally challenged kids with their families with the support of the community. I attended “People First” meetings and became friendly with some of these charming ambassadors living with their families of origin, or in small community-based housing. It was better than what I saw by far.

We’d learned by then the more stimulation challenged kids gets in the first few years, the better their chances later. It was also admitting the best place for a kid is usually at home. At the same time, it was forcing families to take greater responsibility for their offspring, despite the problems, but with support from the state. With that, the stigma of the retarded child began to disappear. I like to believe I witnessed that turning point when my little buddy and his bliss board won his court case.

As for me, I kept applying for release and getting shot down. Each week or two, I’d appear before the warden flanked by two guards and make my case. He’d say no, and compliment me on my improved story, with a smirk on his face. Off I’d go to my dorm.

Then a miracle happened: a prison strike. The Canadian Army were called in to man the security of the province’s prisons. And you guessed it: anyone with an application for early release or transfer to a halfway house in town was automatically approved.

I was out again. Fuck you warden.

A few years later, I encountered the guy I shot at a bar, Billy’s on Somerset where I’d taken my new gal for an afternoon beer. He was still dragging one foot as he walked and thanked me for not killing him. Turns out because he admitted he attacked me first from behind in the preliminary hearing transcripts, the criminal compensation board turned him down for any award. Tough break lad.

Besides the kid with the Bliss board, and Stephen the pica, what haunts me most from those times was pulling up every day at the Rideau Regional Centre in our prison bus and seeing a big black hearse at the back of the place. I don’t remember not seeing one there in the months I was privileged to work outside of prison among these brave souls.

Sometimes the worst places teach you the most. Without contrast, what would we know about bliss?

Stay powerful,

Christopher K Wallace

© 2018, all rights reserved.